NEW DELHI: Why did Prime Minister Narendra Modi choose the heart of Mithilanchal — not Patna, not Magadh — to launch the NDA’s campaign for Bihar’s upcoming assembly elections? The choice was steeped in both sentiment and strategy.

The symbolism was unmistakable. PM Modi invoked the legacy of socialist stalwart and former chief minister Karpoori Thakur — an icon among the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) and a unifying figure across castes. “Karpoori Thakur ji devoted his life to the upliftment of the poor and backward. His ideals continue to guide us,” he said, striking an emotional chord in a region that reveres Thakur as one of its own. Thakur, who once contested elections from Phulparas in the Mithilanchal region, hailed from the EBC community — a dominant political force in the area. Interestingly, this seat was once speculated to be Tejashwi Yadav ’s second choice, underlining its enduring political weight.

The rallies, described within the NDA as the “first step towards Patna,” marked more than just the beginning of a campaign. They reflected a carefully crafted outreach anchored in Mithilanchal’s social history and its decisive 80 assembly seats out of Bihar’s total 243. By fusing the language of development and legacy, the BJP sought to remind voters of its delivery record while positioning itself as the natural inheritor of Bihar’s backward-class leadership.

In choosing Mithilanchal to start his Bihar push, PM Modi wasn’t merely addressing crowds — he was invoking memory, identity, and numbers, all at once. The message was clear: the road to Patna, and perhaps to power, begins in Mithila.

Why PM Modi began his campaign in Mithilanchal

Bihar’s political geography can be divided into five major regions—Tirhut, Mithilanchal, Kosi-Seemanchal, Magadh, and Bhojpur — each with unique demographic compositions and voting patterns. Among them, Mithilanchal stands out not only for its size but for its electoral weight. Spread across districts such as Madhubani, Darbhanga, Samastipur, Saharsa, and Supaul, the region is home to a mix of Maithil Brahmins, Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims, and EBCs — a combination that mirrors the state’s social diversity.

Also read - Bihar elections 2025: Castes, coalitions, and calculations - how numbers stack up

The 2020 assembly elections proved the region’s political volatility. While the NDA scraped through with a narrow majority statewide, its performance in Mithilanchal was pivotal to that victory. In the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, the BJP and its ally, the Janata Dal (United), won all seven parliamentary seats from the region, reaffirming its strategic centrality.

Yet, this loyalty is far from permanent. In 2015, when Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) joined hands with Lalu Prasad Yadav’s RJD and the Congress under the Mahagathbandhan, the alliance swept Mithilanchal—JD(U) won 19 seats, RJD 14, and Congress 11—highlighting the area’s swing nature. This cyclic pattern of shifting allegiances has prompted the BJP-led NDA to return its campaign focus here. As analysts note, the “road to Patna runs through Mithila.”

Samastipur: The EBC nerve centre and Karpoori Thakur’s legacy

The selection of Samastipur as the starting point was both sentimental and strategic. The district, birthplace of Karpoori Thakur, holds deep symbolic weight in Bihar’s backward-class politics. It also reflects the fluid electoral currents that have defined Bihar’s past decade.

Of Samastipur’s 10 assembly seats, political allegiance has consistently swung between the NDA and the Mahagathbandhan. In 2010, the BJP won both its contested seats, while the JD(U) dominated the rest. In 2015, when Nitish Kumar crossed over to the Mahagathbandhan, the BJP was wiped out here. Five years later, with JD(U) back in the NDA fold, the coalition won five of ten seats, with the RJD close behind.

This oscillation mirrors the unsettled nature of the EBC vote. The EBC community, comprising 112 sub-castes and representing 36% of the state’s population, remains fragmented despite its numerical strength. Only a handful of these sub-groups, like the Nais, Kumhars, Kahars, and Nonias, have enough concentration to decisively tilt electoral outcomes.

Karpoori Thakur’s influence continues to shape this narrative. During his tenure in the 1970s, he pioneered backward-class empowerment through a reservation commission that expanded affirmative action for the poor and marginalised. “Karpoori Thakur gave the poor and backward a sense of dignity,” PM Modi said in Samastipur, positioning the NDA as Thakur’s ideological successor. The BJP hopes this emotional appeal will help unite the scattered EBC vote under its banner.

Begusarai : North Bihar’s ideological crossroads

From Samastipur, PM Modi travelled to Begusarai, a district often dubbed “the Leningrad of Bihar” for its Leftist past and ideological churn. Over time, Begusarai has seen shifts from communist dominance to RJD strongholds and now a growing BJP presence.

The BJP-JD(U) alliance dominated Begusarai in 2010, winning six of seven seats. In 2015, the Mahagathbandhan’s resurgence reversed those gains. By 2020, both alliances split the honours, each winning two seats, indicating the district’s increasing fragmentation.

For the NDA, Begusarai represents a litmus test, whether its twin appeal of caste inclusivity and development outreach can bridge ideological divides. With urbanisation, industrial aspirations, and young first-time voters reshaping Begusarai’s demographic profile, the BJP hopes to leverage PM Modi’s “double-engine” development narrative to reassert control.

Beyond caste: Development as a political currency

PM Modi’s Bihar campaign is not anchored solely in caste arithmetic but in development symbolism tied to Mithilanchal’s cultural identity. Over the past few years, the BJP has invested heavily in public projects across north Bihar to strengthen this narrative.

In 2024, Union home minister Amit Shah laid the foundation of the Mata Janki Temple at Punauradham (Sitamarhi), believed to be Sita’s birthplace. The Rs 883-crore project, spread over 67 acres, is envisioned as a major spiritual and tourism centre. Shah also flagged off the New Delhi–Sitamarhi Amrit Bharat Express, improving rail connectivity in the region.

Also read - Delhi, Jharkhand ... and now Bihar: BJP looks to corner Mahagathbandhan over 'infiltrators' - will the strategy work?

Earlier this year, PM Modi inaugurated projects worth over Rs 2,000 crore, including the civil enclave at Darbhanga airport (costing Rs 912 crore) and the AIIMS Darbhanga, the state’s second AIIMS, built on 187 acres at an estimated Rs 1,264 crore.

The 2025 Union Budget further expanded this outreach with the announcement of a Makhana Board, aimed at boosting the globally recognised Mithila makhana. The initiative targets districts like Darbhanga, Madhubani, Saharsa, Supaul, and Sitamarhi, blending economic potential with cultural pride.

Together, these projects underline BJP’s bid to weave developmental nationalism into the regional fabric transforming cultural pride into political loyalty.

Opposition counter-offensive: Mahagathbandhan’s regional campaign

The Mahagathbandhan, comprising the RJD, JD(U), Congress, and Left parties, has mounted a vigorous counter-campaign in north Bihar. Its “Voter Adhikar Yatra” covered large parts of Mithilanchal and Kosi-Seemanchal, with leaders targeting both PM Modi and Chief Minister Nitish Kumar over unemployment, migration, and agrarian distress.

However, the yatra ran into controversy during its Darbhanga leg, where alleged abusive remarks against the Prime Minister drew sharp condemnation from the NDA. BJP leaders accused the Opposition of “insulting Bihar’s cultural ethos,” sparking days of political confrontation.

Meanwhile, RJD leader Rabri Devi revived calls for a separate Mithilanchal state, a sentiment occasionally echoed by local cultural groups. Though the idea finds little traction among mainstream parties, it keeps the emotional narrative of Maithil identity alive—one that both alliances are trying to harness in their own ways.

2023 caste survey: Understanding the math behind Bihar’s caste matrix and the 36% EBC factor

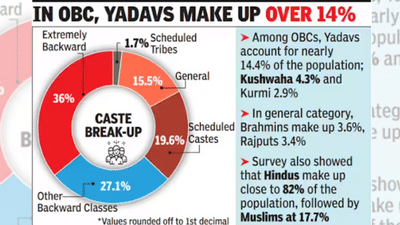

PATNA: The Bihar government’s 2023 caste-based headcount offers critical context to PM Modi’s EBC outreach. The survey revealed that the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) form the largest social group at 36% of Bihar’s 13.07 crore population. Combined with the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) at 27%, these two categories account for nearly 63% of the state’s people underscoring why caste arithmetic drives every major alliance.

Muslims constitute 17.7%, while the so-called “upper castes” traditionally the BJP’s stronghold comprise 10.6%, divided among Brahmins (3.7%), Rajputs (3.4%), Bhumihars (2.9%), and Kayasthas (0.6%).

The NDA’s caste network is built around smaller caste consolidations: Dusadhs/Paswans (5.3%) through the factions of Pashupati Kumar Paras and Chirag Paswan; Kushwahas/Koeris (4.2%) through Upendra Kushwaha and state BJP chief Samrat Choudhary; and Musahars (3%) through the Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular) of Jitan Ram Manjhi.

For the Mahagathbandhan, chief minister Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) relies on EBC loyalty, while the RJD banks on Yadavs (14.3%) and Muslims (17.7%), together forming a formidable social alliance.

Interestingly, the survey showed that Kurmis, Nitish Kumar’s caste group, account for just 2.9% of Bihar’s population. Still, JD(U)’s influence extends beyond caste through Nitish’s personal credibility among backward communities.

Conducted in two phases and released by senior officials led by development commissioner Vivek Kumar Singh, the survey was officially termed a “caste-based headcount” rather than a “caste census” to avoid legal complications, as the law permits only the enumeration of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The data revealed that Bihar’s demographic balance has remained broadly stable since colonial times. In 1901, the “upper castes” made up 15.6% of the population, middle castes (Koeri, Kurmi, Yadav) 19.8%, and Muslims 16.1%. The 2023 survey shows only marginal variations, reaffirming the persistence of caste-based social structures in Bihar.

The caste-based headcount has also fuelled a national political debate, with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and other members of the INDIA bloc demanding a nationwide caste census. Several states, including Maharashtra and Odisha, have expressed interest in conducting similar surveys.

Election arithmetic and the EBC strategy

Polling for Bihar’s 243 seats will be held in two phases - November 6 and November 11 — with counting on November 14. The final electoral roll lists 7.42 crore voters, reduced from 7.89 crore after 65 lakh names were removed for duplication or ineligibility.

In 2020, the BJP contested 110 seats, winning 74 with a 19.8% vote share. The JD(U) contested 115 and won 43, securing 15.7% of votes. Together, with smaller allies like the Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular), the NDA scraped a narrow majority.

This time, the alliance’s focus is firmly on the EBC vote bank — a constituency of more than one-third of Bihar’s population. With OBCs mostly aligned, Dalits split, and Muslims backing the Mahagathbandhan, the EBCs have become the ultimate swing bloc that could decide Bihar’s political future.

Political analysts suggest that the BJP’s current narrative—rooted in EBC representation, cultural revival, and infrastructure development—is designed to neutralise anti-incumbency and counter Nitish Kumar’s traditional social coalition.

The political road ahead

As Bihar gears up for its high-stakes assembly polls, PM Modi’s early campaign in Samastipur and Begusarai reflects more than electoral enthusiasm, it represents a strategic recalibration aimed at reclaiming the social coalitions that have historically defined Bihar’s politics.

By blending Karpoori Thakur’s legacy, development symbolism, and EBC-focused arithmetic, the NDA is attempting to craft a narrative that transcends caste polarisation while still acknowledging its political centrality, which might shift in the second phase of the election post November 6.

Whether this strategy can hold against the Mahagathbandhan’s entrenched backward-class alliance will determine not just the fate of Bihar’s 2025 elections but also shape the national discourse around caste and representation.

For now, PM Modi’s rallies have made one thing clear — winning Bihar begins with winning Mithila, and the path to power runs through its 36 per cent EBC electorate.

The symbolism was unmistakable. PM Modi invoked the legacy of socialist stalwart and former chief minister Karpoori Thakur — an icon among the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) and a unifying figure across castes. “Karpoori Thakur ji devoted his life to the upliftment of the poor and backward. His ideals continue to guide us,” he said, striking an emotional chord in a region that reveres Thakur as one of its own. Thakur, who once contested elections from Phulparas in the Mithilanchal region, hailed from the EBC community — a dominant political force in the area. Interestingly, this seat was once speculated to be Tejashwi Yadav ’s second choice, underlining its enduring political weight.

The rallies, described within the NDA as the “first step towards Patna,” marked more than just the beginning of a campaign. They reflected a carefully crafted outreach anchored in Mithilanchal’s social history and its decisive 80 assembly seats out of Bihar’s total 243. By fusing the language of development and legacy, the BJP sought to remind voters of its delivery record while positioning itself as the natural inheritor of Bihar’s backward-class leadership.

In choosing Mithilanchal to start his Bihar push, PM Modi wasn’t merely addressing crowds — he was invoking memory, identity, and numbers, all at once. The message was clear: the road to Patna, and perhaps to power, begins in Mithila.

Why PM Modi began his campaign in Mithilanchal

Bihar’s political geography can be divided into five major regions—Tirhut, Mithilanchal, Kosi-Seemanchal, Magadh, and Bhojpur — each with unique demographic compositions and voting patterns. Among them, Mithilanchal stands out not only for its size but for its electoral weight. Spread across districts such as Madhubani, Darbhanga, Samastipur, Saharsa, and Supaul, the region is home to a mix of Maithil Brahmins, Yadavs, Dalits, Muslims, and EBCs — a combination that mirrors the state’s social diversity.

Also read - Bihar elections 2025: Castes, coalitions, and calculations - how numbers stack up

The 2020 assembly elections proved the region’s political volatility. While the NDA scraped through with a narrow majority statewide, its performance in Mithilanchal was pivotal to that victory. In the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, the BJP and its ally, the Janata Dal (United), won all seven parliamentary seats from the region, reaffirming its strategic centrality.

Yet, this loyalty is far from permanent. In 2015, when Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) joined hands with Lalu Prasad Yadav’s RJD and the Congress under the Mahagathbandhan, the alliance swept Mithilanchal—JD(U) won 19 seats, RJD 14, and Congress 11—highlighting the area’s swing nature. This cyclic pattern of shifting allegiances has prompted the BJP-led NDA to return its campaign focus here. As analysts note, the “road to Patna runs through Mithila.”

Samastipur: The EBC nerve centre and Karpoori Thakur’s legacy

The selection of Samastipur as the starting point was both sentimental and strategic. The district, birthplace of Karpoori Thakur, holds deep symbolic weight in Bihar’s backward-class politics. It also reflects the fluid electoral currents that have defined Bihar’s past decade.

Of Samastipur’s 10 assembly seats, political allegiance has consistently swung between the NDA and the Mahagathbandhan. In 2010, the BJP won both its contested seats, while the JD(U) dominated the rest. In 2015, when Nitish Kumar crossed over to the Mahagathbandhan, the BJP was wiped out here. Five years later, with JD(U) back in the NDA fold, the coalition won five of ten seats, with the RJD close behind.

This oscillation mirrors the unsettled nature of the EBC vote. The EBC community, comprising 112 sub-castes and representing 36% of the state’s population, remains fragmented despite its numerical strength. Only a handful of these sub-groups, like the Nais, Kumhars, Kahars, and Nonias, have enough concentration to decisively tilt electoral outcomes.

Karpoori Thakur’s influence continues to shape this narrative. During his tenure in the 1970s, he pioneered backward-class empowerment through a reservation commission that expanded affirmative action for the poor and marginalised. “Karpoori Thakur gave the poor and backward a sense of dignity,” PM Modi said in Samastipur, positioning the NDA as Thakur’s ideological successor. The BJP hopes this emotional appeal will help unite the scattered EBC vote under its banner.

Begusarai : North Bihar’s ideological crossroads

From Samastipur, PM Modi travelled to Begusarai, a district often dubbed “the Leningrad of Bihar” for its Leftist past and ideological churn. Over time, Begusarai has seen shifts from communist dominance to RJD strongholds and now a growing BJP presence.

The BJP-JD(U) alliance dominated Begusarai in 2010, winning six of seven seats. In 2015, the Mahagathbandhan’s resurgence reversed those gains. By 2020, both alliances split the honours, each winning two seats, indicating the district’s increasing fragmentation.

For the NDA, Begusarai represents a litmus test, whether its twin appeal of caste inclusivity and development outreach can bridge ideological divides. With urbanisation, industrial aspirations, and young first-time voters reshaping Begusarai’s demographic profile, the BJP hopes to leverage PM Modi’s “double-engine” development narrative to reassert control.

Beyond caste: Development as a political currency

PM Modi’s Bihar campaign is not anchored solely in caste arithmetic but in development symbolism tied to Mithilanchal’s cultural identity. Over the past few years, the BJP has invested heavily in public projects across north Bihar to strengthen this narrative.

In 2024, Union home minister Amit Shah laid the foundation of the Mata Janki Temple at Punauradham (Sitamarhi), believed to be Sita’s birthplace. The Rs 883-crore project, spread over 67 acres, is envisioned as a major spiritual and tourism centre. Shah also flagged off the New Delhi–Sitamarhi Amrit Bharat Express, improving rail connectivity in the region.

Also read - Delhi, Jharkhand ... and now Bihar: BJP looks to corner Mahagathbandhan over 'infiltrators' - will the strategy work?

Earlier this year, PM Modi inaugurated projects worth over Rs 2,000 crore, including the civil enclave at Darbhanga airport (costing Rs 912 crore) and the AIIMS Darbhanga, the state’s second AIIMS, built on 187 acres at an estimated Rs 1,264 crore.

The 2025 Union Budget further expanded this outreach with the announcement of a Makhana Board, aimed at boosting the globally recognised Mithila makhana. The initiative targets districts like Darbhanga, Madhubani, Saharsa, Supaul, and Sitamarhi, blending economic potential with cultural pride.

Together, these projects underline BJP’s bid to weave developmental nationalism into the regional fabric transforming cultural pride into political loyalty.

Opposition counter-offensive: Mahagathbandhan’s regional campaign

The Mahagathbandhan, comprising the RJD, JD(U), Congress, and Left parties, has mounted a vigorous counter-campaign in north Bihar. Its “Voter Adhikar Yatra” covered large parts of Mithilanchal and Kosi-Seemanchal, with leaders targeting both PM Modi and Chief Minister Nitish Kumar over unemployment, migration, and agrarian distress.

However, the yatra ran into controversy during its Darbhanga leg, where alleged abusive remarks against the Prime Minister drew sharp condemnation from the NDA. BJP leaders accused the Opposition of “insulting Bihar’s cultural ethos,” sparking days of political confrontation.

Meanwhile, RJD leader Rabri Devi revived calls for a separate Mithilanchal state, a sentiment occasionally echoed by local cultural groups. Though the idea finds little traction among mainstream parties, it keeps the emotional narrative of Maithil identity alive—one that both alliances are trying to harness in their own ways.

2023 caste survey: Understanding the math behind Bihar’s caste matrix and the 36% EBC factor

PATNA: The Bihar government’s 2023 caste-based headcount offers critical context to PM Modi’s EBC outreach. The survey revealed that the Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) form the largest social group at 36% of Bihar’s 13.07 crore population. Combined with the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) at 27%, these two categories account for nearly 63% of the state’s people underscoring why caste arithmetic drives every major alliance.

Muslims constitute 17.7%, while the so-called “upper castes” traditionally the BJP’s stronghold comprise 10.6%, divided among Brahmins (3.7%), Rajputs (3.4%), Bhumihars (2.9%), and Kayasthas (0.6%).

The NDA’s caste network is built around smaller caste consolidations: Dusadhs/Paswans (5.3%) through the factions of Pashupati Kumar Paras and Chirag Paswan; Kushwahas/Koeris (4.2%) through Upendra Kushwaha and state BJP chief Samrat Choudhary; and Musahars (3%) through the Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular) of Jitan Ram Manjhi.

For the Mahagathbandhan, chief minister Nitish Kumar’s JD(U) relies on EBC loyalty, while the RJD banks on Yadavs (14.3%) and Muslims (17.7%), together forming a formidable social alliance.

Interestingly, the survey showed that Kurmis, Nitish Kumar’s caste group, account for just 2.9% of Bihar’s population. Still, JD(U)’s influence extends beyond caste through Nitish’s personal credibility among backward communities.

Conducted in two phases and released by senior officials led by development commissioner Vivek Kumar Singh, the survey was officially termed a “caste-based headcount” rather than a “caste census” to avoid legal complications, as the law permits only the enumeration of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The data revealed that Bihar’s demographic balance has remained broadly stable since colonial times. In 1901, the “upper castes” made up 15.6% of the population, middle castes (Koeri, Kurmi, Yadav) 19.8%, and Muslims 16.1%. The 2023 survey shows only marginal variations, reaffirming the persistence of caste-based social structures in Bihar.

The caste-based headcount has also fuelled a national political debate, with Congress leader Rahul Gandhi and other members of the INDIA bloc demanding a nationwide caste census. Several states, including Maharashtra and Odisha, have expressed interest in conducting similar surveys.

Election arithmetic and the EBC strategy

Polling for Bihar’s 243 seats will be held in two phases - November 6 and November 11 — with counting on November 14. The final electoral roll lists 7.42 crore voters, reduced from 7.89 crore after 65 lakh names were removed for duplication or ineligibility.

In 2020, the BJP contested 110 seats, winning 74 with a 19.8% vote share. The JD(U) contested 115 and won 43, securing 15.7% of votes. Together, with smaller allies like the Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular), the NDA scraped a narrow majority.

This time, the alliance’s focus is firmly on the EBC vote bank — a constituency of more than one-third of Bihar’s population. With OBCs mostly aligned, Dalits split, and Muslims backing the Mahagathbandhan, the EBCs have become the ultimate swing bloc that could decide Bihar’s political future.

Political analysts suggest that the BJP’s current narrative—rooted in EBC representation, cultural revival, and infrastructure development—is designed to neutralise anti-incumbency and counter Nitish Kumar’s traditional social coalition.

The political road ahead

As Bihar gears up for its high-stakes assembly polls, PM Modi’s early campaign in Samastipur and Begusarai reflects more than electoral enthusiasm, it represents a strategic recalibration aimed at reclaiming the social coalitions that have historically defined Bihar’s politics.

By blending Karpoori Thakur’s legacy, development symbolism, and EBC-focused arithmetic, the NDA is attempting to craft a narrative that transcends caste polarisation while still acknowledging its political centrality, which might shift in the second phase of the election post November 6.

Whether this strategy can hold against the Mahagathbandhan’s entrenched backward-class alliance will determine not just the fate of Bihar’s 2025 elections but also shape the national discourse around caste and representation.

For now, PM Modi’s rallies have made one thing clear — winning Bihar begins with winning Mithila, and the path to power runs through its 36 per cent EBC electorate.

You may also like

'Birth-based ruling class': Dynasts lead candidate lists in Bihar elections; old families still call the shots

Kerala: NHAI condoles man's death in landslide, says it warned of danger days earlier

"Addicts harassing family members": BJP's Jaiveer Shergill blames Punjab govt of "neglecting" drug issue

Jharkhand: 5 thalassemia-affected children test HIV positive after blood transfusion; 3 officials suspended, probe ordered

'Will defend ourselves': Netanyahu says Israel needs 'no approval' to strike foes; claims veto on Gaza force members